review originally published in Phroom Magazine

Hypermarche – Novembre is the third volume from The Gould Collection, a beautifully designed series bringing together the work of writers and photographers in memory of the late photobook collector Christophe Crison. There are five poems by Michel Houellebecq and three bodies of photographic work by Motoyuki Daifu arranged in Hypermarche – Novembre. Three bodies of work that are neatly distinct if overlapping. You feel their edges. There are downward facing still-lifes of food on tables, a family in a densely packed home, and tranquil, if askew, exteriors. The still-lifes and family images feel cluttered and flattened; a personal world, messy, full and bleeding off the edges. Everything is at hodgepodge angles and pressed together, every person caught in some motion, cats and food containers, objects, consumable and not, sometimes human.

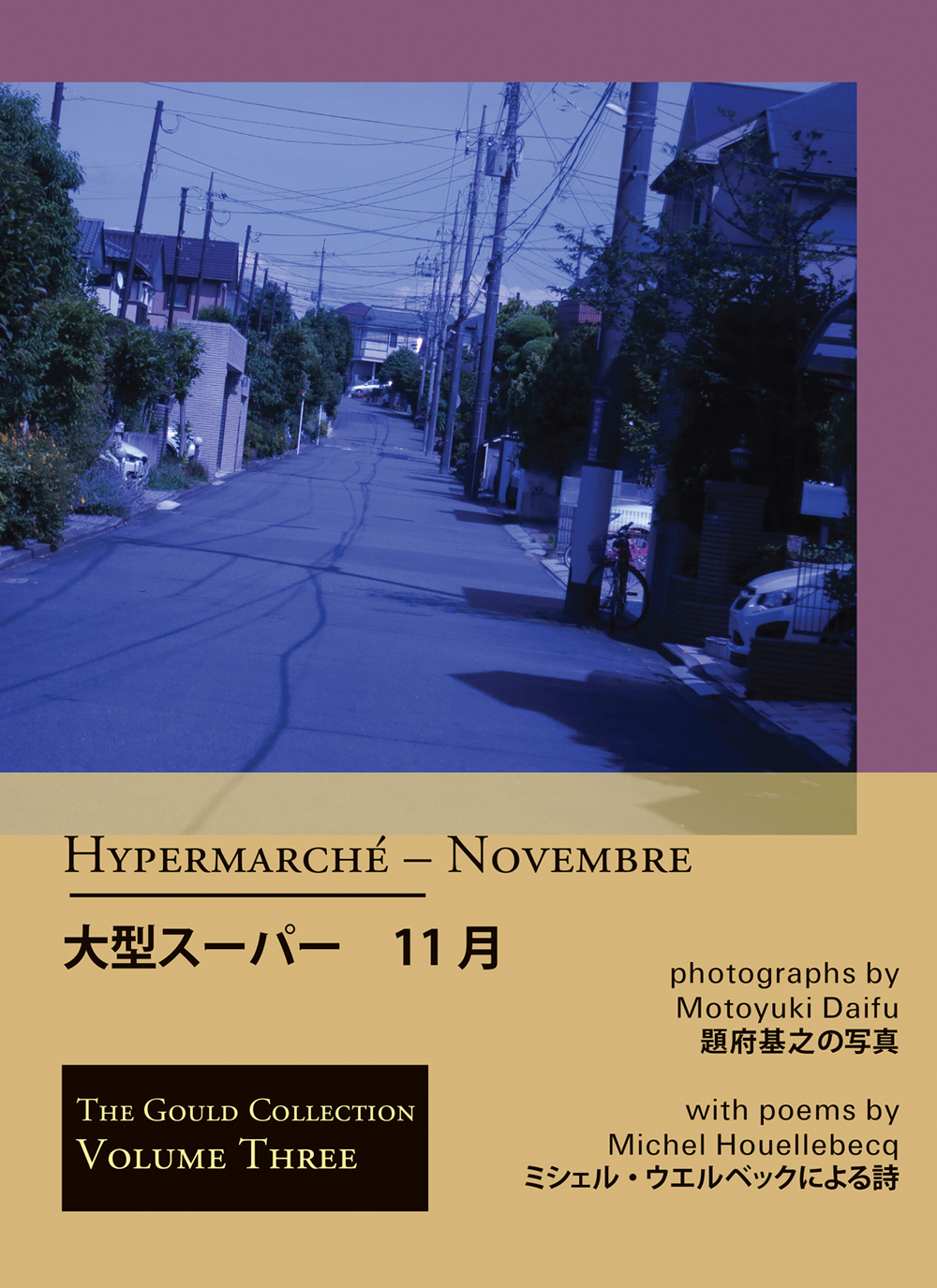

The exterior images are cool and dyed in pale colors like easter eggs, the outer wrapping to these jumbled domestic scenes. I know the cover says “Novembre” but the whole thing feels springtime to me, that bare-pre-blossom cold, the cruel part of spring that may as well be the indication of a second winter. These outside images act almost like blocks of color and intermix with the lavender and gold of the cover and pages of poetry, hued like crocuses breaking through snow. They are a respite from the disarray, despite being a little bit off as well. Leave the house to wander down a frosty street with hands balled up in pockets, eyes are slightly blurred; none of the lines are quite straight.

The golden pages where the poems by Michel Houellebecq are printed (in French, Japanese and English) leaf through the book creating intervals. The texture of these pages is something like nice stationary, also domestic but contrasting; the book’s overall tactile quality lends a fineness that the subject matter lacks. The five poems are highly visual and go together and don’t, finding tangents of internalised description as big as the universe. They overlap each other like Daifu’s photo series, but their movement from super(hyper)market to shoes on the speaker’s feet to Eucharists and embodied destinies and mornings ends with the gesture of a white curtain falling on a stage and is far more expansive. Both Daifu and Houellebecq’s voices emerge as individuals in the midst of chaotic worlds, but I find no further likeness. When paired, the sense of scale of each is confusing.

These are not images that many people would choose to view. This home is unglamorous, unarranged–or maybe arranged, the proximity of items and angles so meticulously disordered, so maybe yes, maybe no. Regardless, the result is not a fashionable haphazardness. The images feel raw and in that way they feel real, or maybe true. These are not images that many people would choose to make. When I’ve seen images like this in the past, images with this level of collection and chaos; they carry a presumption of judgment. Daifu’s images still remain in a state of self-conscious presentation, but I don’t feel judgment here, I feel ownership. This is his family, and his pride and humor and shame and melancholy, as well.